Millions of dollars of ratepayers’ money has been spent installing and running CCTV systems, but the eyes on our streets are not necessarily making us any safer. Farah Hancock reports.

The cameras have won, according to one civil libertarian. They peer down from poles, peep out from under awnings and perch atop doors. Attempting to escape their gaze is futile.

"They're cheap, they're everywhere and I can't see them going away," Thomas Beagle of the NZ Council for Civil Liberties says.

There are more than 10,000 CCTV cameras surveilling public outdoor spaces in New Zealand, a fleet of digital eyes owned by local or central government agencies. Some are in place to monitor traffic, weather or flooding, but most commonly they’ve been installed for security.

In our biggest city, Auckland Transport and Auckland Council own about 5685 cameras combined

This amounts to four cameras per 1000 residents, and that doesn't include the cameras owned by Waka Kotahi, police, businesses, or installed at private properties. They're omnipresent.

Take a stroll through the shared car and pedestrian portion of Fort Street, in downtown Auckland, and you’ll be filmed by 21 different cameras in a space of about 100 metres.

Watch the Fort Street video below:

It’s not just Auckland that’s peppered with cameras. There are eyes in the streets of almost every district in the country.

To map the location of publicly-owned cameras which capture footage of outdoor public spaces RNZ sent Official Information Act (OIA) requests to almost 100 different organisations.

The below map shows the approximate locations of some of the cameras capturing footage of outdoor public spaces.*

Most of us would be unaware of the sheer number of cameras filming us as we go about our daily lives, mistakenly believing ourselves unobserved. Is there a good reason for all these cameras? Are they achieving their purpose? How much are we spending on them? And have we given up our privacy too easily?

Feel uncomfortable at the thought of being filmed? You’re not alone. Forty-one percent of New Zealanders are concerned about CCTV and facial recognition technology.

Acting Privacy Commissioner Liz MacPherson gets it. “From our experience there’s nothing like putting up CCTV or surveillance cameras to get a strong reaction. For that reason we strongly recommend that people and agencies use them cautiously and follow the rules.”

Liz MacPherson, Deputy Privacy Commissioner (Photo: Supplied)

Liz MacPherson, Deputy Privacy Commissioner (Photo: Supplied)

Those rules come courtesy of the Privacy Act. But RNZ’s research found not all authorities are abiding by it, even though breaching the Act can result in a penalty of up to $10,000.

MacPherson is at the coalface of complaints, many of which could be avoided if organisations followed the rules.

"Any organisations that are contemplating using CCTV should carry out a privacy impact assessment that considers things like what will be filmed, whether that information is really necessary for the agency to carry out its work, how the agency will inform the public that they've been recorded - via signage, publishing CCTV policies on the website - and how the recorded footage has been kept safe and secure, including controlling who has access."

The commission has published guidelines covering what organisations should take into account before they install cameras. (The guidelines don’t apply to cameras installed in people’s homes, which can film significant portions of public space, too.)

The guidelines are prescriptive. The first step suggests identifying why you’re installing cameras. “Clearly state the purpose or purposes of your CCTV system. When you do so, make sure you are specific. For instance, if your purpose for using CCTV is to prevent crime, explain the types of crime you seek to prevent.” Doing so, it says, will help organisations comply with the law, and make it easier to assess whether the system is successful or not.

But some of the organisations that responded to RNZ’s OIA requests don't have policies covering their cameras’ objectives, data protection, rules around sharing footage, and policies vetting any volunteer staff monitoring the cameras. According to the Privacy Commission, these are essential to protect people’s privacy

MacPherson warns that those organisations ignoring the policies could face compliance action.

She also queries why some councils are installing cameras if they don’t have objectives - or, if they do, why the councils aren’t reviewing whether the cameras are achieving them.

"I would have thought that ratepayers would be asking, 'Is the CCTV camera system delivering the promised benefits, and does it actually justify the expense and maintenance'?"

Trevor Bradley was at a social event when he got chatting to a CCTV camera salesperson. Bradley’s a senior lecturer at Victoria University of Wellington, and specialises in crime. The salesperson didn’t know this, says Bradley, and was proudly espousing the virtues of security cameras.

“He was telling me about how fantastic these cameras are, and how they prevent crime and so on. I let him go on for a little while.”

When Bradley told the salesperson what his research focuses on, the conversation ground to a halt.

Trevor Bradley (Photo: Supplied)

Trevor Bradley (Photo: Supplied)

According to Bradley, there's scant evidence cameras deter crime.

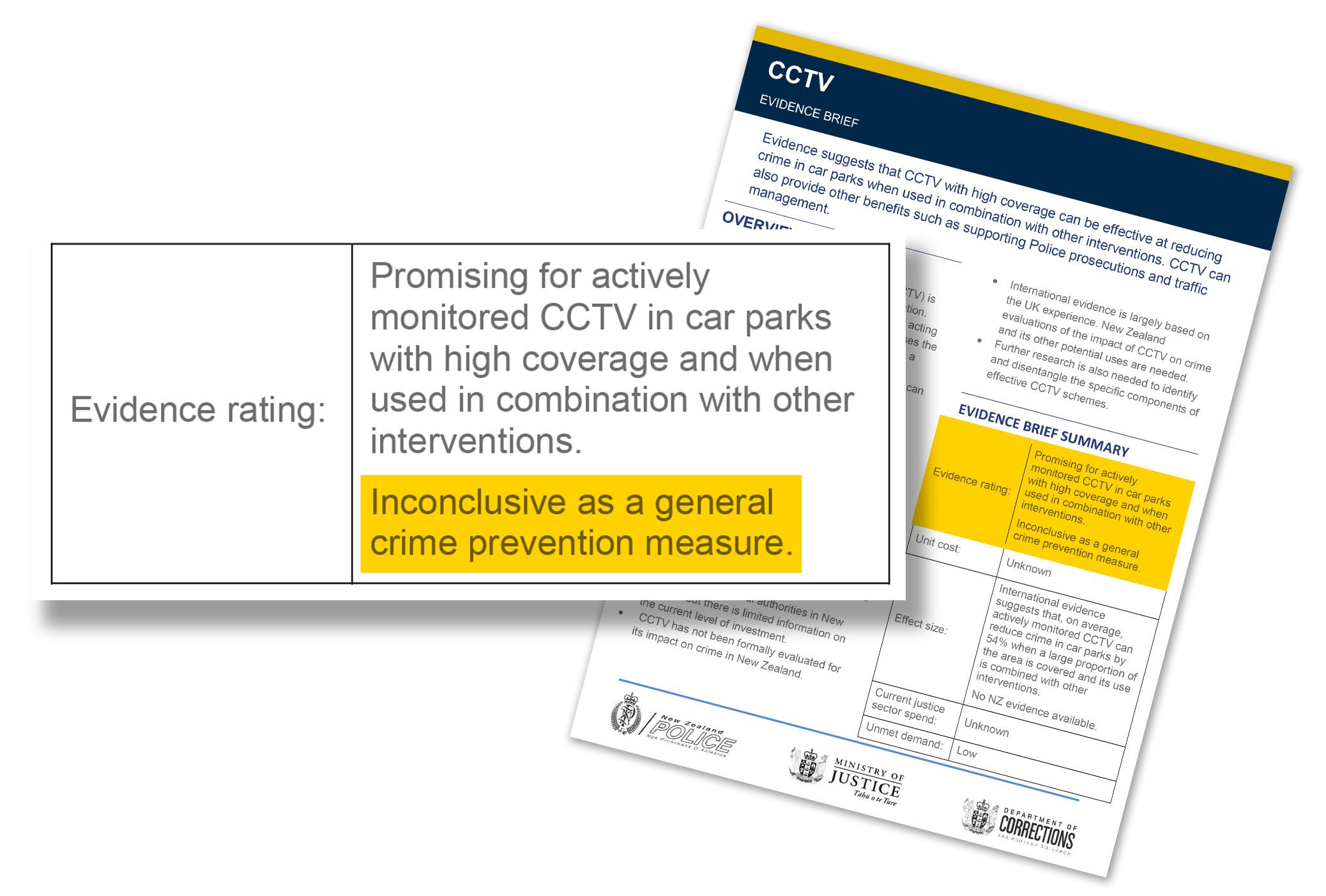

"There's virtually zero evaluation of CCTV from a crime prevention perspective in New Zealand," says Bradley. Overseas research shows CCTV only deters crime in very specific circumstances.

In fact, CCTV has only been shown to reduce crimes in car parks, and only when cameras are combined with improved lighting and other measures, such as security guards.

When it comes to preventing crimes like assault, the use of cameras doesn't stack up, especially over time. Sometimes crime drops after cameras and signage are installed, but the effect wanes over time. Bradley suggests when signs have been in place for a while, they become like wallpaper, and people just don't notice them.

He says the reason people think cameras will deter crime is based on an assumption that people are rational and care about getting caught. But they’re often not. It’s the reason CCTV in areas with pubs and bars is largely ineffective.

"People are not rational when they've consumed large quantities of alcohol, or when emotions are running high. They are completely oblivious to CCTV in those situations."

Bradley thinks encouragement from police is one of the reasons CCTV has become so widespread.

"In my experience, a lot of the growth of CCTV in New Zealand has been because of pressure from police. Local authorities often talk about being in partnership with police. And the police have been huge advocates of CCTV, so they've put a lot of pressure on local councils to invest in them."

Compared to many councils, police own surprisingly few cameras filming outdoor public spaces - just 45. Police refused to confirm or deny that it encourages councils to install CCTV cameras at their own cost. A police spokesperson would only say some councils already have systems.

“Police partner with these local authorities to utilise this to identify suspects, [for] evidence gathering, or preventing crime and disorder."

But police did endorse an evidence brief, published in 2017 by the Ministry of Justice. This found there was inconclusive evidence on whether CCTV prevents crime anywhere but car parks.

Bradley says the lack of evidence that CCTV prevents crime has led some countries to give up on cameras. In the United Kingdom, there was a push for CCTV installation until around 2015, when a change of attitude occurred, partly driven by the austerity movement.

"So they said, 'Well, what needs to go away because we've got to slash millions of budget?' 'Well, I'll tell you what, let's get rid of some of the CCTV because, you know, they're not doing anything.'"

Solving crime and jailing offenders doesn’t necessarily translate to preventing future crime either.

He says the cliche about prisons being a university for crime holds true. People who serve prison time are more likely to offend again. As he puts it, "prison is a criminogenic factor. It's not a crime prevention initiative".

Bradley recommends ratepayers ask councils how they measure whether cameras are effective at preventing crime.

"At the very least, one would have thought before you spend half a million dollars they would have built in some kind of evaluative component."

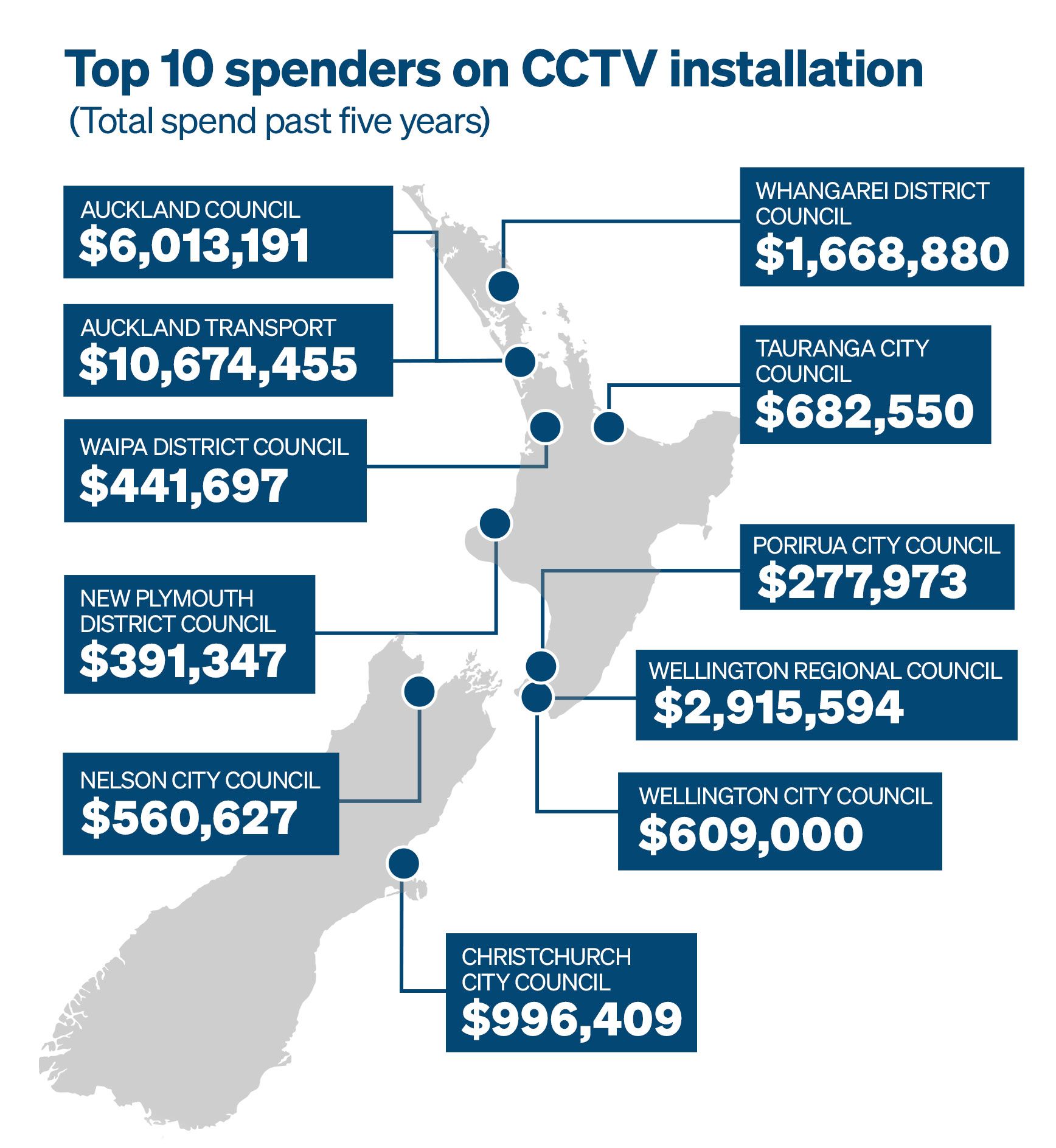

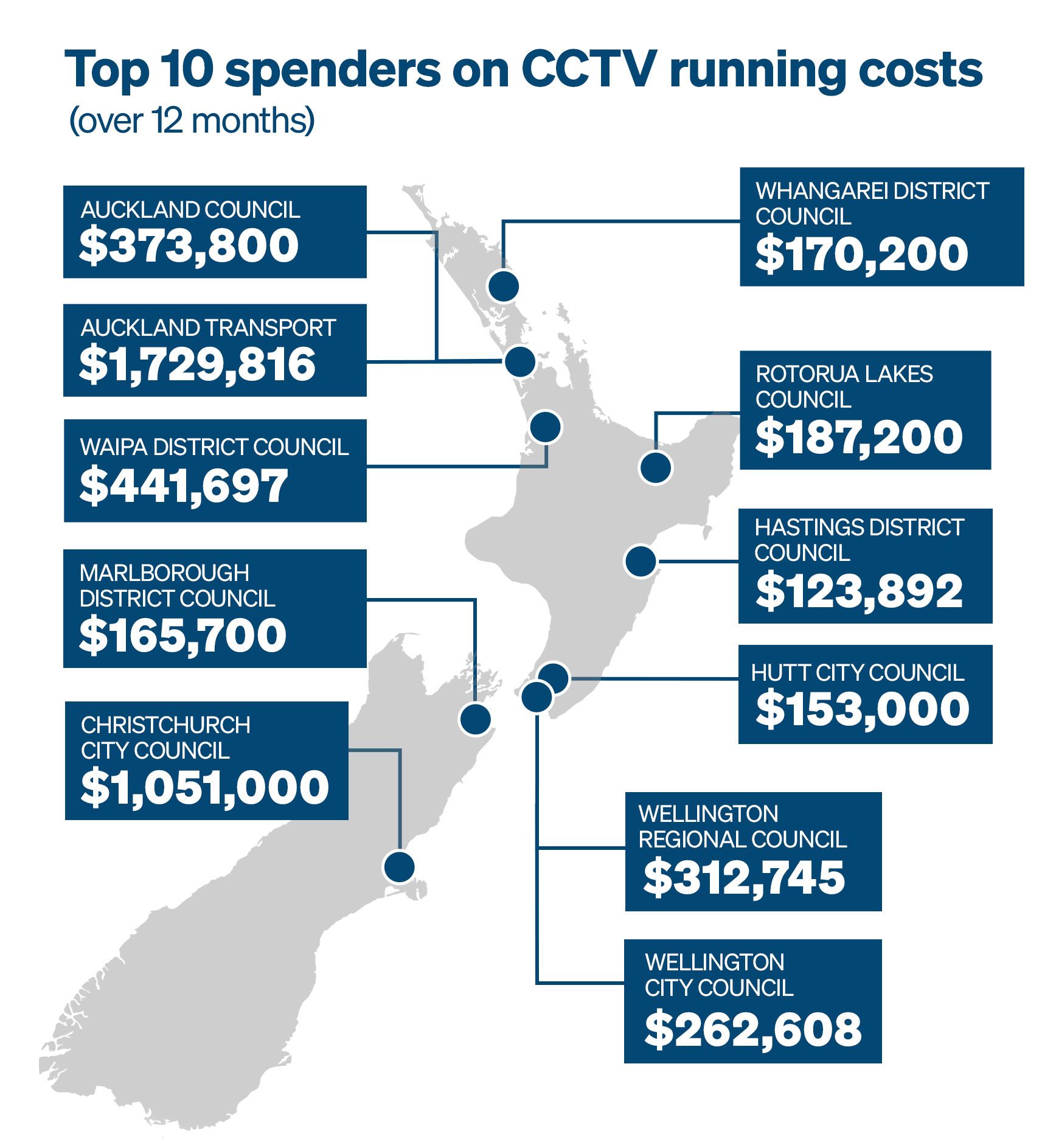

Indeed, taxpayers and ratepayers have spent millions on installing and running CCTV systems.

And the above totals don’t even capture the full amount of money spent. Some organisations RNZ approached wouldn’t or couldn’t share what they had spent installing cameras in the past five years.

The Ministry for Social Development, which has more than 3000 indoor and outdoor cameras, said it was too much work to collate the costs. Waka Kotahi/NZTA, which owns more than 1600 cameras, said it can't break out the costs of installing or running cameras from other expenses. Some councils changed financial systems in the past five years, so could only supply part of the costs. Others had so few cameras installed they said sharing the cost would breach commercial sensitivity. Some didn’t respond to the OIA request.

The biggest spender, Auckland Transport, forked out more than $10 million on installing cameras in the past five years, some of which are used to generate fines.

Running costs vary widely between organisations, with some paying over $100,000 per year, and others saying the only ongoing cost was electricity.

Despite the cost of installation, and the annual cost of running cameras, not all organisations run reviews to ascertain if their cameras achieve their objectives.

Some of the cameras are installed to monitor shipping channels to ensure they are clear from obstructions. Others track wildlife, or traffic congestion.

However, responses to RNZ’s OIA requests show the most commonly cited reason for camera installation is security. Some councils that have installed cameras for security say they rely on police to tell them whether cameras are performing their objective.

Wellington City Council, Queenstown Lakes, Whanganui, Waimakiriri, Masterton and New Plymouth district councils look to police for feedback on whether the systems are preventing crime.

A police spokesperson says area managers believe CCTV "added a level of reassurance for the community as whole" and that cameras can also be a deterrent. "Some noted that any preventative effect was difficult to quantify because CCTV is just one of the tools that Police employ to keep the community safe. "

But some areas have seen increases in crime in the past five years. Police data on victimisations in New Plymouth shows an increase of 32 percent from 2017. During this time $390,000 was spent on camera installation. Each of the other councils also had increases.

It’s not just academics like Trevor Bradley who say CCTV systems aren't a quick-fix solution to reducing crime.

Lincoln Potter has been in the security game for three decades; he’s done retail security, trained security officers and close protection teams, studied security sciences, and the New Zealand Security Association suggests him as the person to talk to about CCTV .

He’s an independent consultant now, and describes himself as a realist. “I'm not going to blow smoke in your face and tell you lies.”

Sometimes he’s found himself caught between CCTV system vendors and clients. He’s not always popular with vendors, as he has no qualms telling clients if they’re being offered a system with unnecessary bells and whistles.

Lincoln Potter (Photo: Supplied)

Lincoln Potter (Photo: Supplied)

Sometimes, he’s brought in too late to stop unneeded spending.

“It's not common - but it's not uncommon - for me to talk with facilities managers that are almost in absolute tears, because they believe they've made the right decision on purchasing $200,000 worth of equipment, that doesn't really work, because they had had an incident and the cameras have all been set on detection and observation, not recognition and identification.”

The terms he uses - detection, observation, recognition and identification - relate to how close-up footage is. If your camera is set to detect, you might see someone breaking into a car in your car park, but the image will be too small to make out facial features and identify the person. If you want to pursue a prosecution, the footage is useless.

*Approximation

*Approximation

He suggests a recent proliferation of cameras is down to people upgrading their systems to include cameras that can supply the type of footage that can be used as evidence. He knows of upgrades where managers have added anywhere between 30 to 60 extra cameras.

But more cameras doesn’t mean a reduction in crime. Potter uses his local superette as an example. “He’s got 17 cameras around his superette, and he’s got a smoke cloak (a device that fills an area with fog).” But these are unlikely to deter someone from jumping the counter and stealing cigarettes.

“So you'd have to ask yourself, well, is CCTV preventing crime? And the answer to that is no. But is it enhancing post evidential requirements? And the answer to that is yes, because you're getting better footage that you can hand on to the police.”

When it comes to cameras in public places, like in a city CBD, good footage can help with identification; but Potter takes pains to point out that when it comes to safety, “surveillance is only as useful as the manpower response to that incident”.

“CCTV and surveillance needs to be supported by a response from a human being: a police officer, a security officer, a city, custodian, or whatever.”

Councils and government organisations can be caught between a rock and a hard place, he says. People want to feel safe in their city and if government and councils don’t increase surveillance, they can be accused of failing in their duty of care.

“It's unfair to throw rocks at the police department and city council for trying to do their best.”

He believes ratepayers could be forgiven for querying whether council spending on CCTV systems is valid, but there’s a catch. While Trevor Bradley says there’s no evidence CCTV prevents crime, Potter says deterrence is tricky to measure.

“If you say, well, where's your return on investment? I would say, ‘Well, good luck trying to measure that, because it's very hard getting quantitative data out of that’. So don't blame them if they can't come up with the figures yet.”

He is concerned, however, at the ever-increasing creep of technology. This includes things like facial recognition, gait-tracking, acoustic monitoring (which can listen for gunshots or breaking glass) or emotion sensing based on a person’s facial expression. He worries they may not always fulfil their purpose. Take emotion sensing. Some people, he points out, have an “angry resting face”.

His concerns may sound far-fetched, but in 2014 Wellington City Council entered into an agreement with NEC, a Japanese company. The city's citizens became lab rats in a short-lived trial of smart city technology aimed at detecting begging in the city centre.

The system included sensors that could smell things like paint fumes, detect sounds such as screaming, and was said to be able to sense if fights may be about to break out.

The agreement with NEC ended in 2018, after the Council spent almost $500,000 on the trial.

Potter says councils have to look at new technology as part of their duty of care. “They’re damned if they do, and damned if they don’t.”

But cameras on every corner capable of mistaking a person with a natural “angry resting face” for someone who might be about to commit a violent crime is not a future he’s keen on.

"To a certain extent, the whole cameras and public debate is over, and the cameras have already won," says Thomas Beagle of the NZ Council for Civil Liberties. "They're cheap, they're everywhere and I can't see them going away."

Thomas Beagle (Photo: Supplied)

Thomas Beagle (Photo: Supplied)

The group believes cameras can have a chilling effect on people's behaviour. Knowing you're constantly being watched can discourage people from participating in activities, such as protests.

"They feel this intimidation, because they feel that they might be being watched and they might be being tracked and [footage] kept and one day it could be used against them."

What’s more, agencies are increasingly linking up systems, while many councils also give Police access to their systems.

In 2021, RNZ revealed the Security Intelligence Service had access to cameras in Auckland, using an arrangement the Privacy Commissioner said was outdated. Auckland Council denied the service was using its cameras but Auckland Transport wouldn’t confirm or deny.

"What are the controls, and who are we sharing it with," are questions Beagle thinks people should ask.

"People kind of think privacy is dead. Google is tracking us, our cell phones are tracking us, there's cameras everywhere, so why don't we just give up and let it all happen? I think that's an incorrect view. I think we do have options we can take and we can pass laws which control things."

Beagle believes current privacy rules aren't robust when it comes to cameras, "but I think we're doing even worse on things like facial recognition".

He would like to see a ban on non-consensual facial recognition use.

Just three councils told RNZ they have cameras with facial recognition enabled. Follow-up questions to two of the councils established the camera footage was of good enough quality to zoom in on faces, but technology to match faces was not enabled. The third council did not respond.

University of Auckland research fellow Dr Andrew Chen says it's reassuring to hear the use of facial recognition technology appears limited.

Chen and Victoria University of Wellington associate professor of law Dr Nessa Lynch recently completed a review into facial recognition technology for the police.

Andrew Chen (Photo: Supplied)

Andrew Chen (Photo: Supplied)

It came in the wake of a scandal, where RNZ revealed police had trialled facial recognition technology in 2020 without clearance. The software, called Clearview, used images from social media sites, such as Facebook.

Later, RNZ raised concerns about police photographing innocent youth and adding their photos to a database. RNZ also revealed police were setting up a different facial recognition system, which could identify people from live CCTV feeds.

Adopting live facial recognition would be especially concerning, says Chen.

“The sorts of scenarios that we're worried about here are things like, where you've got CCTV cameras at a train station, and it's scanning the faces of every person that walks through that train station. If anybody in your top 10 most-wanted list appears, then you immediately send officers down to the train station to apprehend them.”

One of the problems is the software doesn't perform well across all ethnicities. Chen says more research is needed to ensure Māori and Pasifika people aren’t incorrectly matched as wanted people because the software has been designed with lighter skin as the default.

Police must also grapple with a legal question: If police are searching for a particular person, then the use of live facial recognition technology could be considered a search. In that case, it may trigger the Search and Surveillance Act and require a warrant.

Chen says he and Lynch found no evidence police use live facial recognition technology - but the private sector does. At the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, New World supermarket issued an apology after shoppers in its Papakura store were asked to remove face masks as they entered. This was to allow the cameras to scan their faces as part of the store's response to shoplifting issues.

Beyond the ethical and legal issues, there's another big question for law enforcement. Does facial recognition technology actually catch criminals and prevent crime?

"There's a lack of research that's been conducted around policing outcomes," Chen says. "It's uncertain at this stage whether or not using a facial recognition system actually makes societies safer."

Vendors will tout case studies "but a lot of times those case studies are limited and small-scale," he says. Hard data may take a few more years to gather. But for now, Chen says, if you do a cost-benefit analysis the benefit is hypothetical rather than based on real data.

Chen and Lynch’s review contained several recommendations, including hitting the stop button on deploying live facial recognition until several conditions, such as accuracy, could be met. Police adopted the recommendations and the use of live facial recognition software is on ice for now.

Chen's advice to organisations considering using facial recognition technology? Think carefully about whether it's the correct tool to deal with your problem.

"We don't have great rules around what is and isn't allowed with the use of facial recognition."

Acting Privacy Commissioner Liz MacPherson says the Privacy Commission is keeping a "watching brief" on technology.

It recently released a position paper on biometric information which clarifies it expects organisations to take special care if they’re considering using technologies such as facial recognition. The paper will be reviewed every six months.

"The Privacy Act itself is very flexible and technology neutral. To a large extent, it has actually stood the test of time and it can accommodate the changing needs of New Zealand."

Chen agrees with this, but worries the penalties in the Privacy Act aren’t strong enough. He would like to see bigger fines. He’s in favour of strengthening the Privacy Act to give it more regulatory weight.

Security expert Lincoln Potter thinks that when it comes to CCTV, it’s too late for more regulatory power to have much effect.

“How do you police and monitor it with the amount of cameras that are out there? It's too far gone. It's near on impossible; the genie is out of the bottle.”

Reporting

Farah Hancock

Photography and video

Cole Eastham-Farrelly

Art direction and design

Vinay Ranchhod

Editor

Veronica Schmidt

*This map doesn't include non-fixed cameras, such as those on buses, dash cams, or body-cams. It also doesn't contain cameras owned by the Department of Conservation, or all of Waikato Regional Council cameras, most of which are used for pest detection. Both organisations said supplying this information would require too much work, and that pest cameras are often fixed for a short period of time before being moved to a different location.

Auckland Transport camera locations are based on data from 2018 because its current system isn’t able to output GPS or address locations. Tauranga City Council data only has approximated locations, these have been mapped manually, where possible, but not all locations could be found. Cameras owned by NZTA are not included on the map as the agency is still attempting to output GPS details.

Some organisations have refused to release all, or some of the locations of their CCTV cameras. RNZ has lodged complaints with the Ombudsman's office related to the following agencies: Environment Canterbury, Auckland Council, Hastings District Council, Hauraki District Council, Marlborough District Council, Napier City Council, Ruapehu District Council, Selwyn District Council, Tararua District Council, Christchurch City Council and the Ministry of Social Development.

Data from OIAs received after publishing has been added to searchable tables and the CCTV location map.